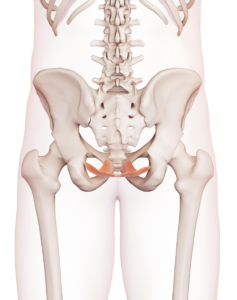

The pelvic floor is a group of muscles, fascia and ligaments that form a hammock-like structure across the bottom of the pelvis. These muscles provide essential support to the pelvic organs, including the bladder, uterus, and rectum, and play a key role in several physiological functions. Understanding their anatomy and function is vital for assessing conditions like pelvic organ prolapse, incontinence, and sexual dysfunction.

The muscles of the pelvic floor are categorised into two main groups: superficial perineal muscles and deep pelvic floor muscles. The superficial perineal muscles are closer to the surface of the perineum and play key roles in sexual function, support of the perineum and contribute to the control of the vaginal and anal openings. The deep pelvic floor muscles form a sling and provide more substantial support for the pelvic organs. This group is primarily referred to as the Levator Ani muscles, which are divided into three key components:

Pubococcygeus: The most front part, which runs from the pubic bone to the coccyx. It supports the pelvic organs and helps maintain continence.

Pubococcygeus: The most front part, which runs from the pubic bone to the coccyx. It supports the pelvic organs and helps maintain continence.- Puborectalis: Forms a U-shape around the rectum, creating an important part of the anal sphincter. It helps maintain fecal continence.

- Iliococcygeus: The more back portion of the Levator Ani, which contributes to the general support of pelvic organs and helps elevate the pelvic floor.

The fascia and ligaments of the pelvic floor play a crucial role in providing passive support to the pelvic organs, working alongside the muscles. Unlike the muscles, however, these structures are not under voluntary control.

The pelvic floor muscles are primarily innervated by the pudendal nerve, which runs from our lower spine. This nerve plays a crucial role in both motor and sensory functions, including voluntary control of urination and defecation.

The pelvic floor has many important functions. One of the primary roles is to provide support for the bladder, uterus, and rectum. This support helps maintain proper alignment and positioning of these organs, preventing prolapse or descent into the vaginal canal. The pelvic floor muscles are also integral to maintain urinary and fecal continence. Additionally, the pelvic floor plays a vital role in controlling continence, as the muscles of the pelvic floor work in coordination with sphincters to manage the release of urine and stool. The pubococcygeus and puborectalis, work together with the urethral sphincter to control the release of urine. When these muscles contract, they help close the urethra, maintaining continence. During relaxation, urination can occur. The puborectalis muscle forms a sling around the rectum, creating the anorectal angle that helps maintain fecal continence. Relaxation of this muscle is necessary for defecation.

Beyond these functions, the pelvic floor is also integral to sexual health, contributing to arousal and orgasm through its ability to contract and relax. Moreover, it acts as part of the body’s core stability system, working alongside abdominal and diaphragm muscles to support the spine and pelvis during movement. This combination of support, control, and stabilization makes the pelvic floor essential for both everyday bodily functions and physical activity.

Pelvic floor dysfunction can arise from various factors that affect the muscles and tissues supporting the pelvic organs. Common causes include pregnancy and childbirth, especially with a larger baby or where there has been a prolonged active stage of labour. These factors can stretch and weaken the pelvic floor muscles and lead to dysfunctions such as SUI and UUI.

Tight pelvic floor muscles can contribute to pelvic floor dysfunction by creating an imbalance in muscle tone and coordination. When these muscles are overly tense or contracted, they can lead to symptoms such as pain, discomfort, and difficulty with urination or bowel movements.

Age-related changes, particularly in women during menopause can also contribute to pelvic floor dysfunction. Estrogen plays a crucial role in maintaining the strength and integrity of the pelvic floor muscles and tissues. This hormone helps promote collagen production and maintain the elasticity of connective tissues, which are essential for supporting the pelvic organs. During menopause, decreased estrogen levels can lead to thinning and weakening of these tissues, increasing the risk of pelvic floor dysfunction.

Chronic respiratory issues and constipation can significantly contribute to pelvic floor dysfunction in several ways. With chronic respiratory problems, such as asthma, individuals experience prolonged coughing, which can place excessive pressure on the pelvic floor muscles. This consistent pressure can lead to weakness or dysfunction over time. This is why you may notice an exacerbation of leakage when you have a cold or hayfever.

Similarly, constipation can create a cycle of straining during bowel movements, which places additional downward stress on the pelvic floor. The muscles may become tight or overactive in response to this straining, leading to a lack of proper relaxation and coordination. Over time, both conditions can disrupt the balance and function of the pelvic floor, increasing the risk of dysfunction.

Dysfunction in the pelvic floor muscles can lead to several issues, including:

- Urinary Incontinence, which is the inability to control urine leakage. There are two main types of urinary leakage: Stress Urinary Incontinence (SUI) and Urgency Urinary Incontinence (UUI). SUI occurs when there is increased downward pressure on the bladder, and the pelvic floor muscles or urinary sphincter are not strong enough to keep urine from leaking. This often happens when you engage in activities that put physical stress on the bladder, such as coughing, sneezing, jumping or laughing. UUI on the other hand, also known as Overactive Bladder, occurs when there is a sudden, strong urge to urinate, and the bladder contracts uncontrollably. This may lead to leakage before you can reach the bathroom. Overactive Bladder occurs when there is a disruption in the communication between the brain and the bladder. Normally, the brain regulates bladder function by sending signals that coordinate the sensation of fullness and the appropriate time to urinate. In OAB, this signalling can become dysfunctional, leading to increased urgency and frequent urination. The brain may also misinterpret signals from the bladder, resulting in a feeling of urgency despite little urine being present. Additionally, psychological factors such as stress and anxiety can exacerbate symptoms by heightening the sensitivity of the bladder.

- Bowel issues, including constipation, diarrhoea, inability to control wind and fecal incontinence.

- Pelvic Organ Prolapse, where there is descent of pelvic organs into or through the vaginal canal due to reduced muscular or fascial support. This can lead to urinary or bowel concerns.

- Pelvic pain and sexual dysfunction.

While consulting a Women’s Health Physiotherapist for a pelvic floor assessment and a personalised treatment plan is always recommended, there are some basic strategies you can try at home to help manage mild symptoms.

First and foremost, it’s essential to prioritise bowel function, even if it’s not your primary concern. Bowel dysfunction can significantly impact other pelvic floor structures, such as the bladder. For instance, if you’re experiencing urinary leakage alongside constipation, the latter may be contributing to the issue. A full, impacted bowel can exert direct pressure on the bladder, leading to or exacerbating the leakage. This is just one example of why addressing bowel function is so important.

Ideally, your bowel movements should be soft and sausage-shaped, allowing for easy evacuation within one to two minutes without straining. Hard stools can lead to constipation, while loose stools can create tension in the pelvic floor. To optimise your stool consistency, consider implementing a few simple lifestyle changes. A diet rich in leafy greens and whole foods, along with adequate hydration, is beneficial for everyone.

If your stools are loose, increasing fibre intake, either through diet or supplements like psyllium husks, can help to bulk them up. Conversely, if you have hard stools, using a stool softener may facilitate easier evacuation. Incorporating fruits like kiwi can also help lubricate the stool.

If you are pushing to defecate, this may be contributing to or exacerbating your symptoms. Therefore avoiding straining during defection is crucial. When defecating, you should lean forwards and use a potty stool to elevate your legs. In this position, the anorectal angle of our puborectalis muscle increases (ie changes from being kinked to straightened), which assists with defecation. Diaphragmatic breathing techniques, also known as belly breathing, can also help to relax the pelvic floor to allow to evacuation. Think about leaning forward, taking a deep breath in through your nose, and out through your mouth. Allow your belly to expand and drop down, and pelvic floor to relax.

Once your bowel function is in order, you can introduce a few additional strategies to help manage urinary leakage. If you find yourself leaking during activities that increase abdominal pressure, like coughing, sneezing, or jumping, consider using “The Knack.” As mentioned earlier, these activities create a strong downward force on the pelvic floor, which can lead to leakage if the muscles are weakened or vulnerable, especially during pregnancy.

Let’s use the example of a sneeze. When you anticipate a sneeze, activate your pelvic floor by squeezing the muscles before sneezing. After you sneeze, you can then relax the pelvic floor. This conscious effort to engage your pelvic floor can be effective in minimising or preventing leakage during such activities.

If urgency is more of an issue, where you suddenly get an overwhelming urge to rush to the toilet, employing some distraction techniques may be beneficial.

Distraction strategies include:

- Curling your toes.

- Lifting your heels off the floor, either in sitting or standing.

- Completing a task that requires moderate concentration, such as writing an email

- Mental distraction strategies such as counting back from 100 in increments of 7.

- Changing positions, such as standing if you’ve been sitting.

It is also important to avoid “just in case” voids. By frequently emptying the bladder unnecessarily, people can unintentionally train their bladder to signal the need to urinate with smaller amounts of urine. Delaying urination, even by a few minutes at a time, helps to gradually stretch the time between bathroom visits, allowing the bladder to fill more completely before signaling the urge.

It’s important to recognize that while these strategies can help many women manage urinary leakage, they might not be sufficient for everyone. A Women’s Health Assessment is essential for a personalised treatment plan, addressing the specific needs of each individual. This assessment provides a detailed understanding of pelvic floor function, muscle strength, and any underlying conditions contributing to incontinence or other pelvic health issues.

If you’re experiencing pelvic floor concerns, booking an assessment with a Women’s Health Physiotherapist at Bend + Mend in Sydney’s CBD is a great step toward appropriate management and recovery.