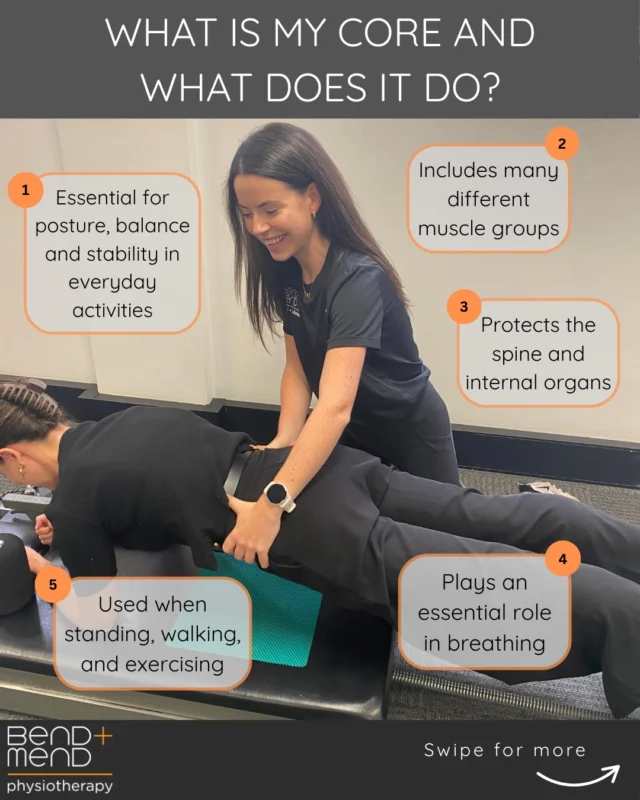

What is your core?

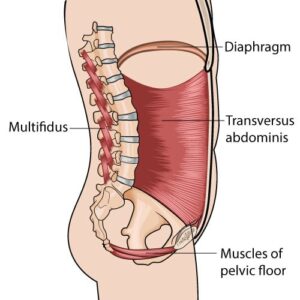

Typically, the core is thought to be your stomach/abdominal muscles, and the belief is that these muscles keep your lower back stable. Well, your stomach muscles are made up of rectus abdominis, external abdominal obliques, internal abdominal obliques (the 3 more outer stomach muscles) and transverse abdominis (the most deep abdominal muscle).

The core musculature that should be doing the majority of the work to keep your lumbopelvic area (spine and pelvis) stable is the inner core. Your inner core is made up from muscles that create a cylinder. These are the diaphragm on top, multifidus and other small deep spinal muscles on one side of the cylinder, transverse abdominis on the other side of the cylinder, and the bottom is made of the pelvic floor.

So only the deepest stomach muscle is part of your core.

What is your pelvic floor?

What is your pelvic floor?

The pelvic floor is part of your core musculature.

The pelvic floor is made of muscles that support your bladder, uterus and bowel.

Function of your deep core muscles verse outer layering muscles.

These deep core muscles are local joint stabilisers, which activate just before you move, to stabilise the segments in your lumbopelvic area. This keeps as even force distribution as possible through these joints, decreasing extra stress through your lower back mainly, but also pelvis and sacral joints.

The outer muscles of your traditionally thought ‘core’ muscles and other muscles of your trunk e.g rectus abdominis (the 6 pack muscle) are what move your trunk, and/or limbs. If these outer trunk muscles play too much of a stabilising role instead of the inner core, more unwanted movement occurs in lumbopelvic area, leading to overuse injuries.

How do transverse abdominis and the pelvic floor musculature work together?

When you inhale, your diaphragm shortens and lowers to expand the lungs. In response, the abdominal wall expands and pelvic floor relaxes, due to the subsequent increase in abdominal pressure.

When you exhale, your diaphragm relaxes while your abdominal wall and pelvic floor contract.

Transverse abdominis and the pelvic floor co-contract together to stabilise your lumbopelic region. They also relax together to control intra-abdominal pressure. Training one will improve the other. Optimally, it’s aimed to have both transverse abdominis and the pelvic floor active while still maintaining normal diaphragm movement with breathing. This motor control in having the right amount of activation at the right times, and enough strength and endurance in these muscles, can all be targeted through exercise.