Pain is most commonly associated with tissue damage or an injury. Given adequate time and assistance from therapists, doctors etc., those tissues in question inflame, repair and remodel (i.e. heal), and the pain goes away. Occasionally however, despite the tissues healing, pain is still experienced weeks, months and maybe years later. It is at this point that the pain experience can be defined as chronic or persistent.

The use of the word persistent is appropriate here as the term “chronic” (as in “chronically unwell” or “chronic unemployment”), suggests that it’s a problem that has to be dealt with and will never go away. This is not the case. Chronic/persistent pain is very much treatable, but unfortunately most treatment fails – sometimes even surgery and medications fail.

Pain is an output of our brain in response to a perceived threat to the body, and the conclusion that action is needed. It is a vital protective response, and is excellent at keeping us safe. This normally goes a little like this:

– tissue damage at periphery eg. a paper cut

– stimulation of a specialised nerve looking for damage (noxious receptor or nociceptor)

– transmission of this “danger message” up the arm, through the spinal cord and into the brain

– in the brain this combines with information regarding mood, emotion, experiences, context and environment

– if it is decided that there is a threat and that it’s a priority, you have the unpleasant experience that is pain

In a persistent or chronic pain scenario, the tissues have healed and are therefore not creating this danger message, or only creating it at a level that would normally not evoke a painful response. Yet pain is still being felt – why? This happens due to changes in the nervous system (the nerves, spinal cord and the brain), resulting in an almost constant perception of threat and the need to act upon this. In essence, the extended experience of pain makes one more likely to experience pain (the exact physiological, neuroimmune and biological reasons for this are beyond the scope of this post).

The problem with approaches to persistent pain is that they are often directed at the tissue in question. If a person in pain is found to have minimal tissue damage, they are often considered a hypochondriac, a malingerer or looking for an insurance payout. These inferences, that the pain is not real, are definitely not helpful. The concept of “all in your head”, which may be interpreted from the above, is also not necessarily correct – treatment would be as simple as telling someone to “snap out of it”, akin to telling one who is depressed to “cheer up”.

What is best for persistent pain sufferers is to understand why they are in pain, identify the causes and not to be afraid of it. Fear implies danger and thus further pain. Five hundred (five thousand or fifty thousand) words are not enough to fully understand pain. I suggest a good starting point is to watch the great video below, and look for an Australian published book called Explain Pain by Butler and Moseley. No one truly understands pain and there is no panacea or cure, but the more you can know about your own pain, the more you understand it and the more your can do about it.

As always, throw any questions or comments in the box below and I’d love to hear from anyone regarding their experiences with pain.

I have pain in my right hand from a triangular fibrocartilage tear at the ulnar styloid attachment.

Will it ever heal if I don’t have surgery?

Hi Arelene, sorry for the slow response but I’ve not long returned from Christmas holidays and I’ve only just had a chance to see your post!

In response to your query, the TFCC is a stubborn structure when it comes to healing, as it’s capacity to heal itself is quite limited due to its cartilaginous make-up. It functions to not only absorb forces through the wrist and to give it a certain amount of stability, but it also helps with the biomechanics of wrist movements. For these reasons, nowadays, at least in Australia, there’s more of a push to salvage as much of the original TFCC when it is damaged rather than surgically intervene if it isn’t affecting these functions; however, this depends a lot on the severity and location of the damage.

With some injuries to the TFCC, there is also a pulling off of the cartilage from its bony attachment (called an avulsion fracture), or additional ligament or muscle injury adjacent to the site of trauma, but even in these situations, conservative management would often be considered your first choice of treatment. Physiotherapists perform this conservative management.

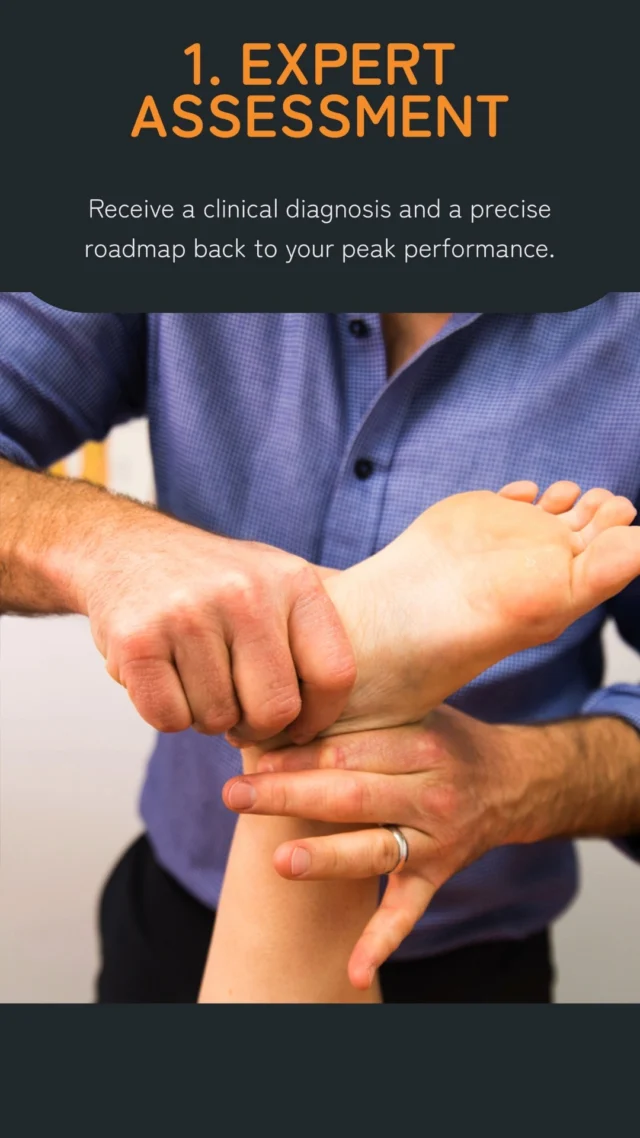

Physio treatment could consist of: splinting/bracing your wrist to stop further damage in the early stages; settling acute symptoms of inflammation (if they exist) with a variety of techniques; prescribing specific muscle strength and stretching exercises particular to your needs; making sure other joints and muscles in your upper limb and spine continue to function well; giving you advice on how to tackle daily home and work activities.

If you’re asking whether it will “heal (without) surgery” meaning, will you ever regain full function of your wrist, then the answer is yes, you can get back to pre-injury function without surgery depending on the factors discussed above. At a local tissue level, however, there’s still likely to be evidence of the damage there, but hopefully no symptoms, loss of function or future problems will arise from it.

I hope this helps you make some decisions, Arlene. Maybe give your Physio a call to discuss it further with them and they may be able to shed more light on the topic as well. Good luck!

Mark.

I partially tore my calf last October, 2012. I’m a professional contemporary dancer and although my recovery wasn’t ideally treated last October, by the end of January 2013 I was dancing at full function and had even began to forget that I ever had a calf injury. But on the 3rd of February I got a terrible cramp in the calf and got a lot of pain after that when I performed. I have now been off for 6 weeks and receiving physio each week. I really believe in the program my physio is leading me through but my progress is stubborn and slow and I truly believe it’s because my mind is refusing to believe I can recover and is full of fear when performing certain movements such as heel raises. So I’m continuing to feel a little pain, muscle dysfunction. aching and lack of progress. Or is it still early in my recovery & these feelings are normal at this stage?

Thank you.

It is relatively early in the rehabilitation process but I would say that you are dealing with more than just a physical injury. I like to use the analogy that your body responds to pain like how we respond to a vaccine. If we get a similar injury in the same spot your body’s awareness is heightened so it will create a similar pain to what you had when you partially tore your calf even if the physical injury is not the same. It’s a very clever trick our body has developed to protect us. To de-sensitise this reaction first of all is important to know it exists and the second part is to gradually expose yourself to those movements that make you most nervous, eg double heel raises. Start at a manageable number of heel raises and consistently repeat that number of heel raises for a week. Initially it might feel sore as your body protects you but as the week progresses and your brain gets used to the exercise it will not need to respond with pain. The following week add a small number of heel raises to your set and continue that number for a week. Gradually your body will realise that heel raises are not a threat and will not respond with pain.

Best of luck with it! If you hit a hurdle, feel free to book in with me and I can run you through a specific programme to get you back on track. Take care, Edel.